Hegemony and "Hate"

Some problems with the discourse of "Hate"

We hear a great deal about something called “hate.” Apparently it is a very serious problem, at the root of a rise in crimes against disadvantaged and “racialized” people. “Hate”, we are taught, is such a serious problem that it must be criminalized, pursued with vigour by the police and the courts, and those guilty of it jailed.

Properly speaking, hatred is an emotion, albeit an unpleasant one. I am not persuaded that hatred is in all cases a bad thing. There are some things deserving of black hatred, or so one might argue. But my point here is not moral, but legal. The problem of “hate” as a legal category is that it imputes an infamous motive to opinions, thereby criminalizing thought and speech. And the set of opinions criminalized as “hate” is large, very large, and growing, as the legal system and those who control it become more ambitious.

The hegemonic ideology designates an opinion “hate,” and with that criminalizes thought, which is obviously wrong. This essay takes two divergent uses of the discourse of “hate,” and contends that they are at root the same problem.

We are now warned by prominent academics that concerns about Chinese interference in Canada’s elections are racist, and the CBC echoes these fears, pointing to year-old figures purporting to show an increase in “hate crimes”. The Chinese government has been happy to smear its critics with these charges, with other supporters of the Liberal Party are not far behind.

There is nothing hateful about criticizing the Chinese Communists. Given our current state of enculturated self-doubt, it is, alas, necessary to emphasize that point. It is in fact pro-Chinese to criticize the Chinese Communists. The current Maoist regime has the shameful distinction of being the direct and avowed descendant of the deadliest regime in history, a regime that outdid in blood both Hitler and Stalin. It deserves all the criticism it can get. And pace the CBC, Canadians are sophisticated enough to know the difference between a regime and a people, just as we can distinguish between Islamic terrorism and Islam, between Russia and Putin.

We also see the imperial character of this category of “hate” in the city of Calgary’s recent by-laws criminalizing protests against drag shows for children. The laws are directly written to criminalize with large fines ($10,000) and jail sentences protests that the mayor dislikes. The law does not criminalize or punish protest for left wing causes. Whether protesters against sexually charged performances in front of children are motivated by hatred is (very) debatable. My point here is that the ever-expanding category of “hate” has grown to include views held by many citizens, indeed views that would have been uncontroversial not much more than half an hour ago. Men like Pastor Derek Reimer have been jailed because of an imputed “hatred.” This is a category that has gone too far.

When first conceived a generation or more ago, laws against hate speech were directed at clear cases of racist and anti-Semitic invective. But now an infinitely ramifying diversity of identity groups, including some of very recent construction, needs to be acknowledged and validated. Our courts being full of activists, scope creep has set in, and it ends with prosecutors trying to keep men like Pastor Reimer in jail for views once common, and even today not usual. In other words, laws criminalizing thought and speech deemed “hate” are being used, with intention aforethought, to coerce opinion in a desired direction.

The CBC report cited above contains figures on “anti-Asian hate”. The adjective “anti-Asian” is as dodgy as the noun, Asia being a big and diverse place. India, to take one example, is not China; the two countries don’t get along well. Even if there were prejudice against the Chinese, or against people who look Chinese, that would hardly extend to Indians or other South Asians, but the CBC puts all apprehended anti-Asian prejudice into one box. The CBC does not believe that Canadians are sophisticated enough to distinguish between the Chinese Communists and the Chinese people, and know that many Chinese people come here precisely to get away from the Chinese Communists.

One of the more annoying things about our self-appointed moral preceptors, of which the CBC is a leading example, is not their leftist ideology but their arrogance, constantly telling us what to think in tones of downward facing patronage, and implying that the rest of us cannot make elementary distinctions. In this propensity to patronize, the CBC is not so distant from Justin Trudeau.

Another problem, annoying because obvious, is an inconsistency of method: when discussing some groups, such as blacks or women, income differences (and other differential standings) are used to infer ipso facto invidious discrimination. But Asian Americans have significantly higher earnings than white Americans, and we have no reason to believe that the situation in this country is different. So, while hate may be a different thing, it is obviously a closely connected thing, and by these standards Asians do not suffer effective discrimination.

But, for the purposes of argument, let us suppose that “anti-Asian hate” is a valid category. The first problem is the problem that afflicts all crime statistics: the numbers will measure crimes reported, not crimes committed, and there are strong incentives both ideological and bureaucratic to report such crimes. No hate crimes were reported in Alabama in 1960, but today we seem to be awash in them. There is good reason to think that these figures reflect social sensibilities more than anything else.

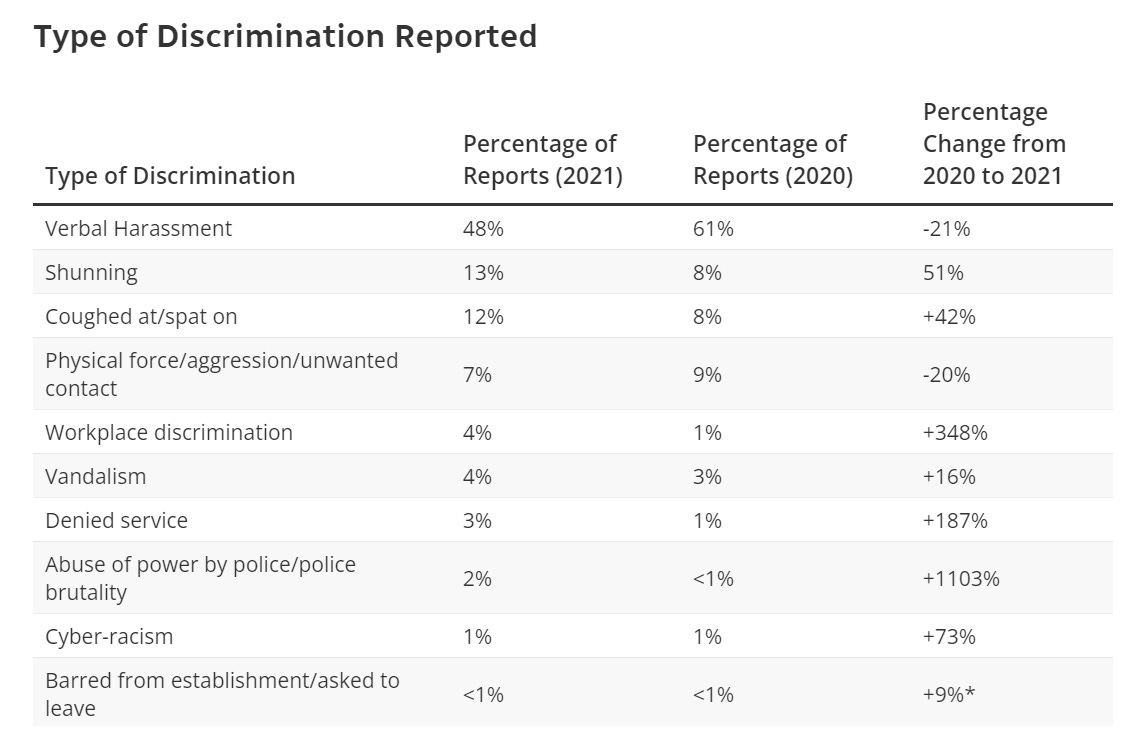

Even if, however, we take the figures at face value, they do not tell the story the CBC thinks they do. I have screen shotted below the top ten kinds of incidents reported. The first type, verbal harassment, making up half the incidents, and has in fact declined. This undermines the central thesis of the article, loudly announced in the title, “anti-Asian hate still on the rise.”

Easily the most serious type of crime here, one that is unproblematically a crime and not merely abusive or unpleasant behaviour, is the fourth, “physical force/aggression/unwanted contact.” This category of serious crime is down by 20% in the year to 2021, and makes up only 7% of reported incidents.

There is a large percentage rise in Police abuse and brutality — 1100%! — but this category constitutes a very small percentage of total cases. But it is a striking figure, however small, and looks like it would make a story on its own, should the CBC be able to find a journalist. But here it is an outlier, and not part of a general pattern.

Source: CBC

The CBC’s figures give a surface impression of empirical support for assertions about “anti-Asian hate,” but actually tell a different, and far from consistent, story. The volume of figures, many pertaining to very small numbers of incidents, itself serves as a distraction.

Another CBC story from Vancouver earlier this year shows racial incidents in that city declining by over half, from 98 to 44 from 2020 to 2022. This is clearly off-message, and not cited in last week’s story.

Very predictably, the CBC calls for government spending on “culturally-specific services,” and “anti-Asian racism education,” along with much about “racial justice.” For the CBC, as for the Liberal Party, as for much of the Ottawa state, spending money is the solution to everything.

These two dissimilar cases of “hate” tell us that the hegemonic left, as here exemplified by the CBC, has a limited set of prefabricated categories into which to fit social problems. The subaltern group of concern is always oppressed by a colonial, capitalist, racist, white supremacist, etc., society, and the problem is rooted (as we are here instructed) in Canada’s baleful colonial past. Add to that the obvious fact that the Chinese interference story helps Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives, and the CBC has a direct material interest in playing down Chinese malfeasance, and in sliming anyone who mentions the topic with the imputation of racism and “hate”. Ideology reinforced by interest make together a powerful combination.

“Hate” is used, in both cases discussed here, in the service of a political end: the movement of social mores in a leftward direction on the one hand, and that plus the suppression of the Chinese interference story on the other. Obviously, the discourse of “hate” was not created for these specific purposes. It already existed; these are articulations or employments, not causes of the discourse. But the discourse of “hate” was created, and has been used aggressively, to mold public discourse in directions desired by the hegemonic ideology. That ideology holds that our society is defined by the oppression of marginalized or vulnerable groups, whose protection requires an assertive bureaucratic and legal regime, including restrictions on thought and speech. The hegemonic power structure behind that legal regime will decide which groups are really marginalized, and which ideas amount to “hate.”

This concept of “hate” has become a tool of power. It is a standing danger to civil liberties, most particularly to our right to critical thought.

There is much more to say about, and against, this standing threat to our most basic liberties, and I shall return to this subject, among other related problems.